This

blogpost is inspired by a recent blogpost by Itztli Ehecatl at Calmecac Anahuac, in which he lays

out the different calendar correlations between the Aztec/Mexica calendar and the gregorian one, and in which he argues in favor of the correlation recently made by Rubén Ochoa. I agree that Ochoa’s correlation is the best available, and

in this blogpost, I describe why that is – recycling some of the arguments from

Itztli Ehecatl’s blogpost and adding others.

|

| Depiction of the Celebration of the feast of Tlacaxipehualiztli during the Spring Equinox in the Codex Borgia (folio 34) |

A recurring question in the study of Aztec calendrics has been whether the Aztec calendar did or did not correct for leap years. Generally the question has been answered in the negative (see e.g. Sprajc 2000). Archaeoastronomer and expert in Mesoamerican calendars Anthony Aveni (2016:110), in his recent chapter on calendars in the Oxford Handbook of the Aztecs, concludes that “there is little evidence that the Aztecs employed a leap-year correction”, but that the question is open.

Rather, I think the question is wrongly posed - who says the Aztec calendar even needed a leap year correction the first place?

The basic

problem is that there is little explicit evidence that the Aztecs used an

intercalary leap year in their xiuhpohualli

solar year count, but also it seems that the monthly feasts, many of which were

related to an agricultural cycle and themes were usually celebrated at the appropriate

time of year for a given agricultural event. This poses a basic question of how

to reconcile the idea of calendric agricultural rituals with a calendar count

that cannot be fixed in relation to the tropical year.

But as I see it the question can be resolved quite simply by recognizing, as several

scholars have, that the beginning of the Aztec year was fixed by the vernal

equinox and that the nemontemi are

simply the days between the end of the 360-day cycle and the beginning of the

next. This would make the question of leap year moot for the Aztec calendar

since the equinox/new year would automatically fix the calendar to the tropical

year every year, and the need to have an explicit principle for intercalating days

or months due to the increasing disjuncture between the astronomical and

calendric year would never arise.

Currently,

none of the most widely accepted correlations between the Aztec calendar and

the Gregorian adopt this solution to the leap year problem. But the solution

emerges naturally from the argument that the vernal equinox marked the

beginning of the Aztec year.

Today, the most

scholars use one of two correlations – Caso’s or Tena’s. Alfonso Caso’s correlation does not correct for the

bissextile year and so does not begin on a specific day relative to the

Gregorian calendar, it would result in the Aztec year starting on a different day each year with the monthly ceremonies gradually changing their position relative to the tropical year. Rafael Tena’s model, in turn, does

correct for leap year, but he argues the year begins on February 26th

with the veintena of Atlcahualo.

Oddly, as noted by Itztli Ehecatl, neither Caso nor Tena cites Nuttall’s 1894 paper or her 1904 article in American Anthropologist in response to Eduard Seler. The argument against the intercalation of an extra day to correct for leap year is that some scholars find that it disrupts the ongoing count of the other calendrical cycles – the 260 day tonalpohualli and the lunar and venus counts. The argument for an intercalary day has mostly been the seemingly correct correspondence with sowing and fertility rituals in the spring months and the harvest rituals in the fall. Some scholars (e.g. Graulich 2002) have argued that the agricultural associations of the monthly feasts were so vague that they didn't really require being performed at a specific time of year (which is debatable), and that farmers don't need a calendar to tell them when to sow and harvest (which is right).

Oddly, as noted by Itztli Ehecatl, neither Caso nor Tena cites Nuttall’s 1894 paper or her 1904 article in American Anthropologist in response to Eduard Seler. The argument against the intercalation of an extra day to correct for leap year is that some scholars find that it disrupts the ongoing count of the other calendrical cycles – the 260 day tonalpohualli and the lunar and venus counts. The argument for an intercalary day has mostly been the seemingly correct correspondence with sowing and fertility rituals in the spring months and the harvest rituals in the fall. Some scholars (e.g. Graulich 2002) have argued that the agricultural associations of the monthly feasts were so vague that they didn't really require being performed at a specific time of year (which is debatable), and that farmers don't need a calendar to tell them when to sow and harvest (which is right).

Nuttall was

the first to propose the equinox as marking the end and beginning of the Aztec solar year. Her

proposal however has been echoed also by Lopez Luján (2005), who argues, based

on the astronomical alignment of the Templo Mayor, and in accordance with

Nuttall, that Tlacaxipehualiztli was the first 20-day month of the Aztec year

and that its beginning was fixed by the equinox.

Recently, Rubén Ochoa has verified that Nuttall’s correlation is consistent with the evidence

from prehispanic calendric codices, and that the length of the nemontemi must have varied so as to

gradually adjust to the tropical year. He notes that the addition of a day is

evident in the relation between the two most securely dated events in Aztec

history: the arrival of Cortés in

Tenochtitlan on November 8th 1519 (2 quecholli/8 ehecatl) and the

fall of Tenochtitlan on August 13th 1521 (15 miccailhuitontli/1 coatl). He notes

that counting from the first date to the second requires at least one

intercalary day, which he supposes would have extended the nemontemi of one of

the two interceding years with one day from 5 to 6 days. The explanation of Ochoa’s model and the evidence from the codices can be found

here and the evidence showing how the model works for the known dates around 1519-1521 is found here.

Nuttall

however, followed the colonial chronicler De La Serna in believing that there was a 13-day intercalary

trecena every 52 years, when the New Fire ceremony was celebrated. But as noted

by Hassig, this would have had the effect of throwing the correlation between

the agricultural year and the calendric year off so much that it would be impractical as an agricultural calendar. Hassig proposes

that rather than resetting directly to the astronomical year, the New Fire

Ceremony reset the year to 7 days earlier than the exact match, which would

mean that the total variance between the agricultural year and the calendar would

vary over the 52-year period, but without becoming greater than about 7 days

which is agriculturally tolerable. The main problem with Hassig’s explanation

is that it is entirely conjectural.

What sets

apart Ochoa’s solution from those of de la Serna, Nuttall and Hassig is that when

following the principle of beginning the calendar year on the day after the observable

equionox, no explicit intercalation is necessary, nor are any calculations or

record-keeping of a deep day count. The

intercalation arises naturally as the number of days between the end of the

360- xiuhpohualli and the beginning

of the next after the equinox naturally varies between five and six days. For the

Aztec commoner, the principle is simply that when the last day of the year is

over, the waiting period for the beginning of the new year begins, and the

waiting period ends when the priests calls that the sun is in the right

position. Calendar priests will be aware that every four years there are six

days before the equinox rather than the usual five, but since the nemontemi are already out of count and

simply fill up the rest of the year, they do not need to make explicit mention

of any “intercalation”, they simply keep counting the tonalpohualli day count

and then restart the year count on the equinox. In this way, the Aztecs had a

smoothly functioning calendar which could function without significant

deviation from the tropical year, and which could be observed in all

communities that shared the custom of beginning the new year on the vernal

equinox, regardless of what month they used as the first in the year.

The Nuttall-Ochoa model has a number of major advantages over all previous calendar models:

The Nuttall-Ochoa model has a number of major advantages over all previous calendar models:

- It solves the leap year problem without the necessity of explaining how the intercalation of days was accomplished without further confounding any existing mismatch between local calendar variants.

- It requires minimal astronomical knowledge to use since it can be maintained as a self-correcting system through the simple cultural practice of beginning the year count the day after the observable equinox, without the necessity of making calculations into the past or future or keeping records of bissextile years.

- It is congruent with the clear cultural relations between the calendar rituals and the agricultural cycle and the close cultural association between the year and the growth period.

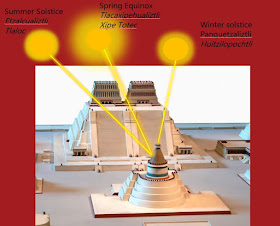

- It is congruent with the archeologically attested importance of the equinox, and with the use of westward-oriented double temples that allow for ease of observation of the equinox sun between the two temples, and which symbolically divides the year into two deities who then represent the estival and hibernal solstices.

- It is linguistically plausible based on the literal and cultural meanings of ‘nemontemi’ (“they vainly fill up”), and ‘xihuitl’ (year/herb/green(-stone)/comet).

- It is congruent with what we know about the practices surrounding the Maya solar calendar, including the architectural use of E groups as observation points from where the vernal equinox can be observed relative to the main temple structures.

- It is congruent with the known correlation dates for the arrival of Cortés in Tenochtitlan in 1519 and the fall of Tenochtitlan in 1521.

To me however the best argument comes from the Templo Mayor and has been used by Leonardo Lopez Luján to argue that the temple was tied to the equinox and to the calendar: If we assume that the Mexica new year started right after observing the spring equinox (usually march 21st in the Gregorian calendar), then the sun would rise exactly in between the two shrines on top of the Templo Mayor. AND: The feast for Huizilopochtli in Panquetzaliztli the sun would fall around the Winter Solstice when the sun would be above the Huitzilopochtli temple, and the feast for Tlaloc in Etzalcualiztli would fall on the summer solstice (during the rainy season in central Mexico). With Ochoa's model, but not with any of the others, this would be the same year after year, without any need to discuss how to put the calendar back in sync with the sun.

Finally, as a treat, here is a link to Calmecac Anahuacs "Aztec Date app" which calculates any given date according to the Nuttall-Ochoa correlation. You can use it to find out what date you were born, married in the Aztec calendar.

Update (28/04/2017): Additional Arguments:

I have been encouraged to also mention the main arguments against the Nuttall-Ochoa correlation, so I will do this here. Traditionally it has been believed that the Aztec year was named after the day-sign (in the tonalpohualli ritual calendar) of the first day in the year. If we follow the Nuttall-Ochoa model, the first day of the year however is not the one that defines the year bearer - rather years seem to be named after the thirteenth day of the new year - this does seem a somewhat arbitrary principle, although thirteen is of course an important number.Also a final argument in favor of the correlation , although a somewhat subjective one, is that in the Nuttall-Ochoa correlation and none of the others, my birthday falls on the Tonalpohualli day 13 Ozomahtli, about which the Florentine codex writes (in Anderson and Dibble's translation): "It was said that anyone who was born upon this day sign became a highly favored person; he succeeded and endured on Earth. He was well respected and recognized; he was famed and honored; hence he was one who prospered, enjoyed glory, was compassionate, and served others. As a chieftain, he was strong, daring in battle, esteemed, intrepid, able, sharp-witted, quick-acting, prudent, sage, learned and discreet; an able talker, and attentive. To everyone he brought happiness, as much as to comfort the afflicted and provide succor. And if such did not befall one, it was said that he himself, by his own doing, neglected and destroyed his day sign through vice, because perchance he took not good heed, perhaps did not perform the penances well.The closing day sign 13 Ozomatli was named Tonacatecutli. And likewise they said that the one then born would become aged; they said that he would finish his work, endure on Earth, and be admired" (Florentine Codex, vol. 4-5:53-54).

Bibliography:

- Aveni, A. F. (2016). The Measure, Meaning, and Transformation of Aztec Time and Calendars. In The Oxford Handbook of the Aztecs (p. 107). Oxford University Press.

- Caso, A. (1967). Los calendarios prehispánicos (Vol. 6). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

- Graulich, M. (2002). Acerca del” Problema de ajustes del año Calendárico mesoamericano al año trópico”. Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl, 33(033).

- Hassig, R. (2001). Time, History, and Belief in Aztec and Colonial Mexico. University of Texas Press.

- Lopez Luján, L. (2005). The offerings of the Templo Mayor of Tenochtitlan. UNM Press.

- Nuttall,Zelia. 1894. Note on the Ancient Mexican Calendar System. Communicated to theTenth International Congress of Americanists in Stockholm. Bruno Schulze.Dresden.

- Nuttall, Z. (1904). The periodical adjustments of the ancient Mexican calendar. American Anthropologist, 6(4), 486-500.

- Sprajc, I. (2000, January).Problema de ajustes del año calendárico mesoamericano al año trópico. In Anales de Antropología (Vol. 34, pp. 133-160). UniversidadNacional Autonoma de Mexico, Instituto de Investigaciones Antropologicas.

- Tena, R. (1987). El calendario mexica y la cronografía (Vol. 161). Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia.

La imagen que sirve de referencia para explicar como el Templo Mayor funcionaba de "gnomon" (según del Paso-Nuttall) resulta ser tendencioso y manipulador. Crea la sensación de que es real, ya que visualmente lo tenemos enfrente, esto es un bulo; la reconstrucción del Recinto sagrado es tentativa, no se sabe en realidad la dimensión de los santuarios en su cima ni donde podrían llegar las sombras de ellos, ¡todo es teórico!

SvarSletMuchas de las supuestas ventajas que encuentras en la teoría de Ochoa en realidad también las puedes encontrar en otras propuestas.

Los códice que considera de fuentes para explicar el supuesto "inicio de año" no fueron usado en el centro de México, son de tradición mixteco-poblano. Están siendo manipulados y no coincide con la interpretación de los estudiosos de escritura prehispánica.

(Soy Akapochtli, te mando información por correo)

No estoy de acuerdo con esa critica. Los detalles del imagen que tal vez necesita modificarse no son significativas relativa al argumento. Aunque no sea el templo de Quetzalcoatl enfrente, todavia es hecho que el sol estaba en esas posiciones relativa al templo para cualquier espectador mirando al piramide de frente en esas fechas.

SvarSletTampoco importa la distancia entre los dos templos et cetera, es hecho que en el equinoccio el sol estaría directamente arriba del centro del templo, y que en los solesticios estaría al lado del templo del dios correspondiente a la fiesta - si seguimos esta correlación.

Te pido que por favor compartas las otras correlaciones que tienen las dos ventajas centrales que tiene este modelo:

1. Falta de necesidad de tener complejas calculaciónes para saber como ajustar el calendario al año tropico - haciendolo solamente con observaciones simples de la posicion del sol.

2. Correlacion entre las fiestas calendricas, y las posiciones del sol relativa a los piramides dobles?

Primero y antes que nada te pido una disculpa, he estado muy ocupado en otras actividades y no pude responder en tiempo como es debido. Sinceramente te ofrezco una amplia disculpa. Espero por otro lado que este tiempo te haya servido para revisar las fuentes y puedas tener los datos más a la mano.

SvarSletSiento como si estuviéramos hablando de cosas diferentes; tu enfoque está centrado en lo práctico del modelo de Ochoa con su respectivo rechazo a "complicados cálculos" para hacer el ajuste del bisiesto; mi enfoque se centra en el consenso de las fuentes para explicar el mecanismo del calendario.

Las objeciones que yo presento al modelo "Ochoa Count" son totalmente válidas, parto de la revisión de su propia “wiki” (http://www.calmecacanahuac.com/tlaahcicacaquiliztli/Ruben_Ochoa_Count) que imagino no es diferente del blog o el post que hicieron en Facebook. Hiciste dos preguntas, en mi opinión demasiado generales y abiertas, en concreto puedo responder que se puede usar investigaciones paralelas para apoyar correlaciones. Los aspectos astronómicos-solares son implícitos y aceptados por todos los investigadores actuales, derivado del desarrollo de la arqueoastronomía a partir de los ochentas, al igual los aspectos rituales-climáticos del ciclo agrícola son considerados por varios investigadores. Tratando de responder directamente presento la siguiente información:

1.- El Templo Mayor u otra estructura como marcador del inicio del año. El primer error de Ochoa es que no considera en realidad la orientación del Templo Mayor, no utiliza la arqueoastronomía. Antes de López Luján ya lo había propuesto como marcador Jesús Galindo, (“Alineación solar del Templo Mayor de Tenochtitlan”. En Arqueología mexicana Vol. VII – Núm. 41, enero-febrero 2000. 26-29) quién señala que el paso del sol entre los dos templos se da el 9 de abril y 2 de septiembre, no el 21 de marzo. Se estructura en una secuencia a partir de la primera fecha de 73 días hasta el solsticio de verano el 21 de junio, luego otros 73 días para su segundo alineamiento (2 de septiembre), para luego pasar un periodo de 219 días (3 x 73) antes de reiniciar el ciclo.; el depender de un momento astronómico para fijar el inicio del año está expuesto a una serie de variaciones:

1.1. El momento astronómico no siempre ocurre el mismo día, en años se adelanta y en otros se atrasa, de hecho así queda demostrado en el mismo trabajo de Zelia Nuttall de 1894 (pp. 34-35, el equinoccio no coincide con el signo cipactli, este coincide con el 24 de marzo).

1.2. La Ochoa Count al querer realizar el ajuste únicamente en los años acatl es una alternativa, validado por sólo una fuente que menciona el bisiesto en malinalli, aunque opuesto a la conclusión de Tena y Castillo Ferraras (basados en un mayor consenso de las fuentes) que lo marcan en los años tecpatl.

2.- La correspondencia entre las veintenas con el ciclo agrícola y astronómico. El estudio de Carmen Aguilera (“Xopan y tonalco. Una hipótesis acerca de la correlación astronómica del calendario mexica”. En Estudios de Cultura Nahuatl, núm. 15, IIH, UNAM, México, 1982 pp. 185-207) complementa bastante bien la correlación de Tena, fechas claves son los solsticios, sobre todo la descripción de Panquetzaliztli por Sahagún; también corresponde la fecha de edificación del Templo Mayor que aparece en una placa arqueológica. También los estudios de Johanna Broda (Arqueología mexicana Vol. VII – Núm. 41, enero-febrero 2000. 48-55) apoyan la correspondencia entre las fiestas y las fechas, y aunque los usa para la correlación 2 de febrero funciona muy bien también para la del 23 de febrero.

Por último, nuevamente te pido disculpas por la tardanza. Al momento de postear esto te envío la información prometida, un par de documentos Word, aunque le faltan observaciones pero la podemos trabajar juntos si gustas.

Te envío un cordial saludo. Zatepan titottazqueh.

Denne kommentar er fjernet af forfatteren.

SvarSletMuchas Gracias Francisco,

SvarSletTu propia critíca inicial no era muy especifica, más bién era un rechazo sin argumento, por lo cuál tuve que hacer preguntas generales para así llegar a la especificidad.Pues ya estamos llegando a lo específico.

1. No es el templo mayor que marca el principio de año - es el equinoccio, y el equinoccio es visible sin el templo. Pero el templo y los demas templos alineados al equinoccio demuestran la importancia de este evento astronómico - y hace que para mi es imposible pensar que el año calendrico no se ajustaba al año solar - cada año. El libro de Lopez Luján aparecio en primera edición en 1994, antes del articulo de Galindo. No se si Galindo tiene razón que pasa en el centro en esas fechas, eso se puede averiguar con observación, pero mi instinto es creerle a Lopéz Luján, y tengo conocidos que han confirmado el paso en el centro de los templos en equinoccio en otros sitios arqueologicos en el centro de Mexico, y es demostrado en sitios Mayas también.

1.1. No importa el tiempo del dia en que occurre el equinoccio, el punto es que la observacion comienza cuando comienza los nemontemi y sigue siendo nemontemi hasta que se oberva el equinoccion.

1.2. Aqui desacuerdo un poco on Ochoa, porque no creo que habia ninguna necesidad de intercalar un biesiesto - se intercalaba solo cuando se seguia el metodo de esparar a empezar la cuenta hasta el equinoccio. No se en que años se insertaba el extra dia, y de mi punto de vista importa poco.

2. No conozco el estudio Carmen Aguiler,a lo voy a leer y ver que contribuirá a mi pensamiento. Conozco bien los estudios de Broda, y su descripción del Tlacaxipehualiztli con cuerda con el analisis de Ochoa y de Lopez Lujan y dice "In case such a sun observatory was actuallly built into the great temple of Tenochtitlan, it would have been possible to correct the calendar every year by the simple observation of the sun’s shadow reaching a straight line. Unfortunately, our sources are, at least for the time being, too faulty in thís respect to permit us te know what the Mexícans really did.". Parece que ella piensa entendió también el principio atrás de la correlación de Ochoa, y considera que es muy probable que el año comenzaba con el equinoccio como lo sugiere Motolinia y Historia de los Mexicanos por sus Pinturas.

Para las fiestas la correlación Ochoa pone la fiesta de Tlaloc en el momento cuando el sol está sobre el templo de Tlaloc, y la fiesta principal de huitzilopochtli en el momento cuando el sol está sobre su templo. No creo que eso sea coincidencia.

Saludos cordiales,

Magnus

Ya te envié el artículo de Aguilera, el libro de López Luján "Las ofrendas del Templo Mayor" no puede enviarlo pues excede de 25 Mb, estoy tratando de subirlo a la nube de Drive o Dropbox.

SvarSletSin embargo leyéndolo encontré (p.77-78) que no apoya una correlación con inicio el 21 de marzo, remarca la importancia del evento vernal pero ACLARA que el Templo Mayor NO está alineado a esa fecha;se alinea a cuatro fechas (y estos datos no son su conclusión, los toma de otros autores: Tichy, Aveni, Ponce de León), López Luján resalta las fechas 5 de marzo y el 9 de octubre, equivalentes al primer día de Tlacaxipehualiztli y del primero de Tepeilhuitl, aceptando la correlación sahaguntina 2 de febrero (12 de febrero gregoriano).

El comentario que trascribes de Broda por supuesto que resalta la importancia del equinoccio pero Broda NO acepta el inicio del año en esa fecha, ella también parte de la correlación de Sahagún.

La propuesta de Nuttall es sumamente incompatible con las crónicas del siglo XVI, ninguna menciona el inicio el 11 de marzo, ninguna habla de un ajuste de 13 días al final del xiuhmolpilli, los códices que mejor explican el mecanismo de combinación xihuitl-tonalpohualli usan los portadores tradicionales para iniciar las veintenas (tochtli, acatl, tecpatl, calli), ninguna menciona un mega ciclo de 1040 años para que vuelvan a coincidir el año civil y el año astronómico.

Como lo mencioné al principio del otro comentario, creo que estamos hablando de cosas distintas; por supuesto que acepto la asociación de los dos santuarios a los solsticios, pero no están directamente alineados, los resultados de Galindo ponen la importancia en el solsticio de verano, las fechas recopiladas por Luján varían apenas en un par de días (7 abril y 5 de septiembre, podemos comparar ambos resultados).

La relevancia de los eventos astronómicos para marcar el inicio del año no es nuevo, podemos ver las propuestas de Veitia y de Orozco y Berra que, basados en las crónicas, ven la relevancia del solsticio de invierno (asociado a Huitzilopochtli) y parten de ahí para establecer sus correlaciones.

En realidad se necesita una revisión minuciosa de las fuentes pero sobre todo entenderlas por sí mismas, esto antes de aceptar propuestas nuevas.

Saludos.

Denne kommentar er fjernet af en blogadministrator.

SvarSlet